The Queen City, incorporated in 1788, is so named for a reason. Hovering just over the threshold of large cities, Cincinnati has a population of 309,513 people. So, despite a sense that Cincinnati is small potatoes (as much by natives as bigger big city folk) we are a big city. Not because of produce, but pork and steamboats. Or, perhaps more accurately because of the interior transportation connections afforded by the Ohio River that allowed moving materials, goods, and people.

The Mississippi is the mother of North American rivers at 3,730 kilometers in length and an average discharge rate of 593,000 cubic feet per second. However, while there are other rivers longer than the Ohio, their discharge pales in comparison to Ohio’s 281,500 cubic feet per second. And tying into the Mississippi, the Ohio River has a direct connection to the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic Ocean. Before there was a car in every garage, and before transcontinental train travel, waterways were our super highway, and snail mail happened via horse and wagon.

This helps frame changes to the ten largest cities that had always been a rotating mix of the original thirteen colonizing cities. New Orleans (served by the Mississippi) was the first departure to that pattern in 1810, likely due to it being the center of the USA Slave Trade before the Civil War. Cincinnati was the first Midwestern city to break onto the list as the eighth largest city in 1830. Moving to sixth in 1840 and staying there in 1850. The Queen City shifted to seventh largest in 1860, eighth in 1870 and 1880, slipping to ninth in 1890, and tenth in 1900, before dropping forever off the list. The Midwestern cities of St Louis joined the list in 1850 and Chicago appears in 1860. Chicago would become the world’s fastest growing city in its first hundred years following its 1833 founding.

This growth was set into motion with Chicago’s first rail, the Galena & Chicago Union Railroad of 1848. Soon followed by tracks that tied Chicago to the existing Midwest rail infrastructure begun in Ohio with the 1936 Erie & Kalamazoo Rail Road which offered east/west transportation to compliment the north/south directions of most canals. The Cleveland Cincinnati Chicago & St Louis Railway was created in 1889 and quickly became known as the Big Four, acknowledging the importance of these urban hubs.

People scoff sometimes when Cincinnati’s 1880s city ranking is referenced. However, while ultimately overshadowed by Chicago, Cincinnati’s seventy year top ten running illuminates much of the infrastructure that we benefit from today, like our parks, schools, and arts institutions. It also may highlight why, after the ideas of Isaac Mayer Wise, immigrant from Bohemia, didn’t go down well in New York, he eventually found his way in 1854 to Cincinnati, the birthplace of the Reform Movement. This Midwestern Jewish hub is home to the first Hebrew Union College, founded in 1875, site of the American Jewish Archives (the largest Jewish archive outside of Israel), and boasts the Skirball Museum (the first formally established Jewish museum in the USA).

Like other big cities Cincinnati had a mix of cultural communities. German and Irish heritage, and the skirmishes between these groups, receives the focus of attention. However, by the 1850s, Cincinnati (at its highest sixth place largest city ranking) boasted 115,000 residents, including 3,200 African Americans, “making it one of the largest Black-American communities in the nation during the antebellum era.”

The challenges of living in a free state across the river from enslavement territory is highlighted in the case of Margaret Garner in 1854, “one of the longest fugitive slave trials in history” and navigating the Black Laws of 1804 and 1807 which required African Americans wishing to migrate into the state to hold a certificate asserting free status and acquire a $500 bond secured by two people “guaranteeing good behavior” among other provisions. These conditions led to the June 30, 1829 race riot that destroyed Bucktown where African Americans resided and exiled about half of the black population who sought asylum in Canada. Another race riot followed in 1841 spurred by a group of primarily Irish dock workers attacking a group of African Americans.

This is some of the historical landscape of the Cincinnati forged a century before the August 28, 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom dawned. The civil rights movement and this groundbreaking event inspired social change movements around the world. 497 Cincinnatians traveled on Tuesday August 27, 1963 by Chesapeake & Ohio Railway from Cincinnati Union Terminal to the District’s Union Station for $20 round trip.

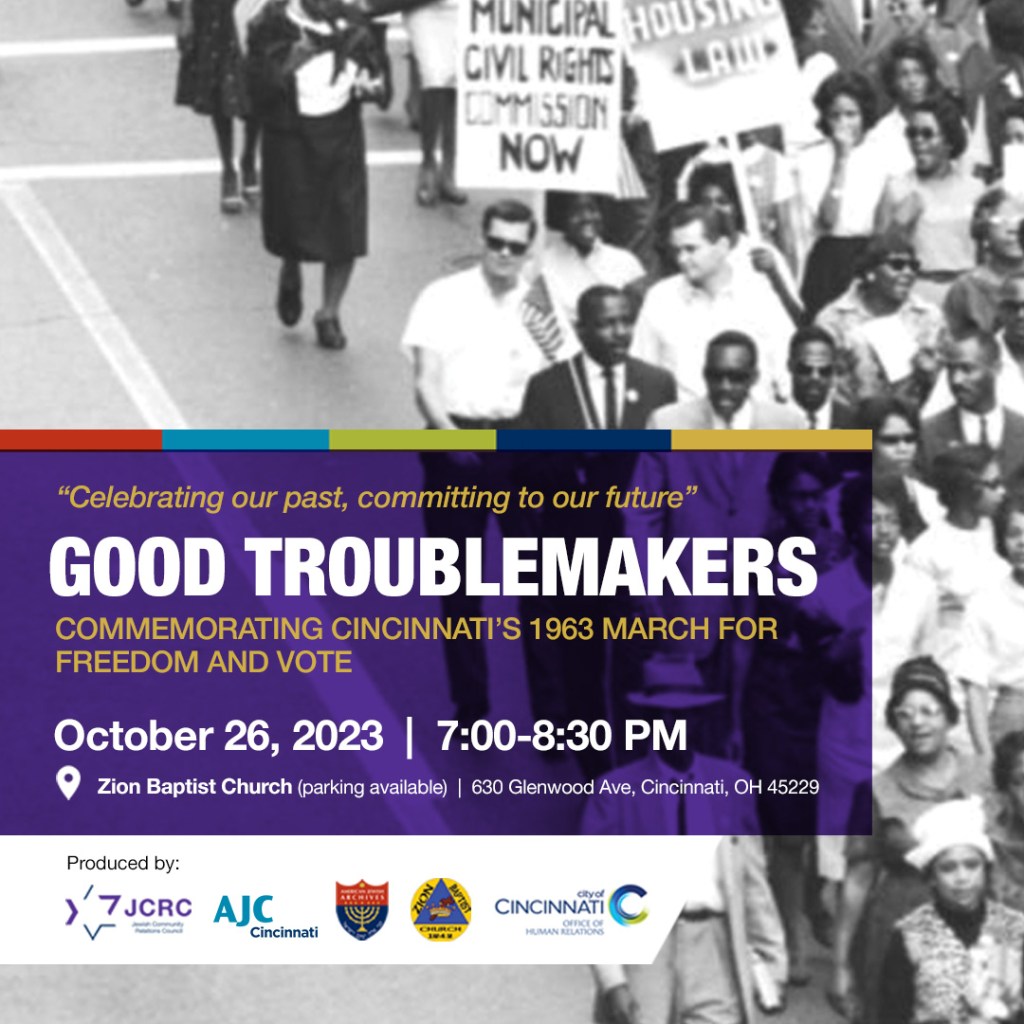

The conditions were ripe in Cincinnati that, upon their return, local leaders organized an October 27, 1963 Freedom March to Fountain Square, inspired by Otis Moss who had in turn been moved by Martin Luther King Jr. It may be conceivable that no one exists who has not heard of the March on Washington. While I am a transplant to Cincinnati from Chicago, I never heard of the Cincinnati march or if organizing marches back home may have been an embedded strategy obscured by the magnitude of the DC event. The continued local momentum, replicated in a march, appears to be a Cincinnati idiosyncrasy.

Unique Cincinnati history abounds. I was at the New York Transit Museum when I learned of Granville T. Woods (born in Columbus Ohio and lived for a time in Cincinnati) who engineered technology a century ago that revolutionized the subway. It was in reading Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi where I heard about Charlene Mitchell (born in Cincinnati), the first black woman to run for President of the United States of America in 1968 as a member of the Communist Party. The internet taught me that Alice King Chatham, a Dayton Ohio sculptor, helped create the earliest helmets for astronauts of the space program. Josiah Henson stayed in Cincinnati for just a few days, but while here influenced Harriet Beecher Stowe’s writing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Just two weeks ago, I learned that Michael W. Twitty lived in Cincinnati when he was young. Our city has claimed things with less intersections. Why are these things I did not know as a resident of such an old city? I look forward to hearing from people who attended both of the 1963 marches and learning more about this proud Cincinnati history.

Jews of Color Sanctuary is honored to partner among seventeen organizations to promote Good Troublemakers commemorating the 60 anniversary of the Cincinnati 1963 March for Freedom and Vote.

The event is free, open to the public, and does not require advance registration. Join us between 7-8:30pm on Thursday October 26, 2023 at Zion Baptist Church located at 630 Glenwood Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio 45229.

“That day, for a moment, it almost seemed that we stood on a height, and could see our inheritance; perhaps we could make the kingdom real; perhaps the beloved community would not forever remain the dream one dreamed in agony.” -James Baldwin

One thought on “Good Troublemakers”